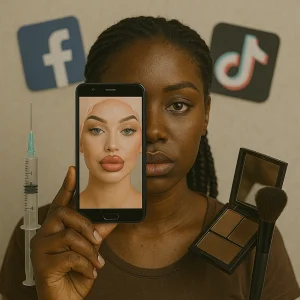

There’s been a surge of online articles and influencer content suggesting a wave of Nigerians abroad are returning home in droves, citing dissatisfaction, racism, or emotional disconnection. But this narrative often skews reality. For most Nigerians overseas, especially those raising families or established in their careers, returning is not on the cards. The question, then, is: Why is the internet full of stories suggesting otherwise?

- Anecdotes Aren’t Trends: Stories of return often come from influencers or privileged professionals who have the social and financial capital to restart in Nigeria—something most migrants don’t. These stories are powerful but not representative.

- Return Is a Choice—Not a Movement: While a few middle-class Nigerians do return for personal or business reasons, there is no tsunami of returnees. The vast majority stay abroad, pursuing education, security, and long-term stability for themselves and their families.

- Migration Realities Are Complex: Life abroad is difficult—discrimination, isolation, and identity crises are real. But so are the benefits: better healthcare, education, legal protections, and freedom. Many Nigerians weigh these trade-offs and choose to stay, not return.

- Privilege Shapes the “Japada” Story: Those with access to networks, seed capital, or dual citizenship often romanticize return. They are insulated from everyday challenges in Nigeria: power outages, insecurity, erratic policies—and can cherry-pick their experience.

Migration is emotional. Even when doing well abroad, many grapple with homesickness, identity, and a longing for belonging. The idea of return becomes symbolic - a way to process dissatisfaction or displacement. Content creators amplify these feelings because they resonate, not necessarily because they reflect mass behavior.

Telling these stories isn’t wrong, but it’s important to contextualize them. Romanticizing return without acknowledging the structural barriers or the privileges of those who do return risks misleading audiences, especially young Nigerians at home or abroad, considering their next move.

One Canada-based Nigerian put it simply: “I miss the food and the culture. But my kids are thriving, I have healthcare, and I can walk outside without fear. I’m not going anywhere.” His story is far more common than the viral return videos suggest.

As migration and mobility reshape identity, the real story lies in complexity, not absolutes. Instead of asking “why are Nigerians coming back?”, perhaps we should be asking “who is telling these stories, and why?”